The USDA and Hemp: What Comes Next?

With the matter-of-fact pronouncement “USDA Establishes Domestic Hemp Production Program,” the Department of Agriculture has officially declared hemp containing no more than .03 percent THC a legitimate crop that will eventually receive all the normal government services, like crop insurance and systematic publication of basic data, that makes commodity markets possible. While there is already spirited criticism from the hemp industry, the draft hemp rule gives farmers struggling with depressed corn and soybean prices, and a ruinous decline in dairy demand, the option of planting a new crop for a growing market.

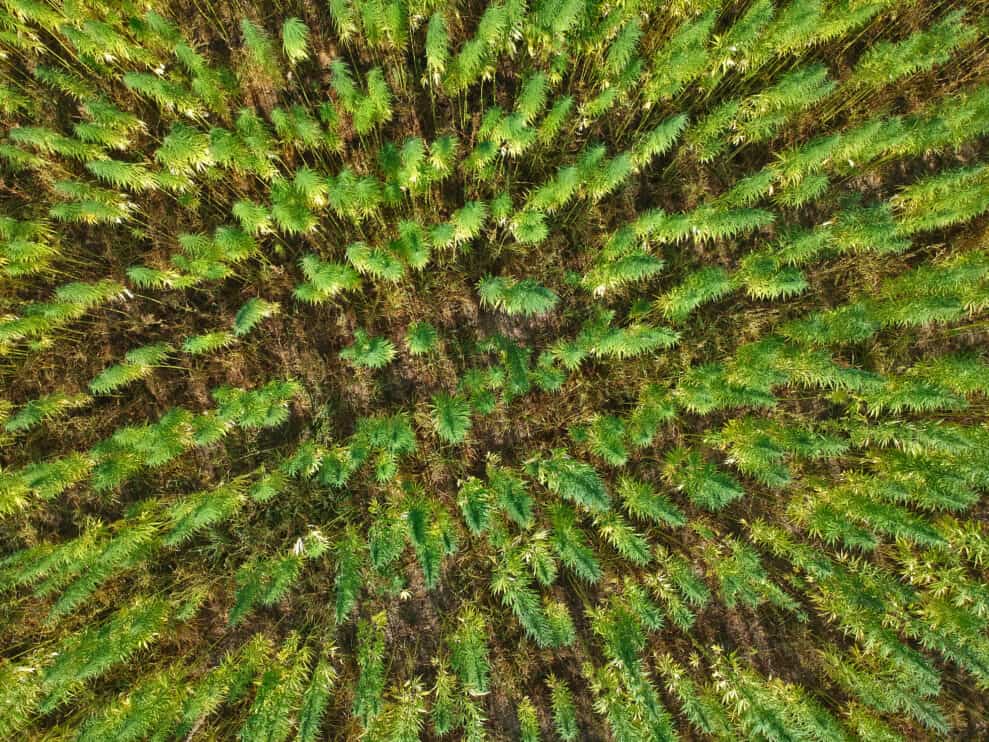

The immense demand for hemp-derived CBD has motivated farmers to embrace the crop. According to the advocacy group Vote Hemp, 9,770 acres of hemp were grown in 2016 under a limited USDA pilot program. In 2018 the number was 78,176 acres. This year, the first planting since the Hemp Farming Act was signed into law, farmers have received licenses to plant 511,442 acres. By giving farmers a defined, though many think unduly onerous, testing process to certify their crop is within the THC limit, the rule is likely to encourage more hemp planting until supply and demand reach equilibrium. There has been a wide range of where that may be given the many uses of the crop, and only time will tell where research will lead us to or consumer demand will pull us towards.

Certified legal hemp

The Hemp Farming Act of 2018 removed hemp containing .03 percent or less THC from Schedule 1. In theory, this immediately made hemp (and presumably CBD derived from it) as legal as a bushel of corn. Legal hemp is indistinguishable from illegal cannabis without lab testing, which has resulted in police mistaking hemp for cannabis.

The hemp farming rule establishes a national laboratory protocol for certifying hemp is within THC limits, a crucial step for allowing routine transport of hemp from field to processor to market.

Putting the USDA hemp certification process into effect will take some time. The labs will have to be DEA certified. The samples of hemp flower must be collected no more than 15 days before harvest by a USDA-approved agent, who could be law enforcement officers. The testing protocol allows for a margin of error, or “measurement of uncertainty” as USDA terms it, to allow for crops marginally above the THC limit. Beyond that, however, crops with excessive THC will be destroyed. It is likely the hemp industry will advocate for more lenient testing and certification protocols, so the final rule could be different. Given the nature of the plant and benign effects of remediating the crop to reduce THC levels, there’s little reason why more leniency wouldn’t be employed other than to create significant waste and loss (hardship for farmers) for no other discernible reason than continued demonization of a useful cannabinoid.

The draft hemp rule marks the end of hemp’s regulatory stigma but USDA has work to do before the crop is fully normalized. A freak hail storm in eastern Oregon late this summer severely damaged 500 acres of hemp worth $25 million. That’s a total loss for the farmers because the USDA crop insurance program doesn’t yet cover hemp. USDA still must specify standard measures and units for hemp, as it has for all other crops. There can’t be a hemp commodity market until there is a measure, like the bushel, for a standard unit of hemp.

CBD as a commodity

Consumer demand for CBD is the economic engine that has driven a 50-fold increase in the amount of hemp planted in the US since the first pilot programs authorized in the Farm Bill of 2013. High prices for CBD-rich hemp encouraged a rapid increase in the number of acres planted and a frantic scaling of the supply chain to process raw biomass into consumer products.

Prices for hemp biomass and the wholesale CBD products derived from it have been dropping recently, a response to the bumper harvest anticipated this year and continued acreage expansion expected as a result of the USDA rule. Consumer demand for CBD is expected to grow. BDS Analytics estimates that US sales of cannabis- and hemp-derived CBD products were $1.9 billion in 2018 to $20 billion by 2024, a compound annual growth rate of 49 percent.

A growing consumer market for CBD products and an abundant hemp supply will require a buildout of the hemp supply chain and is likely to create significant opportunities, such as specialized farm equipment and building the DEA-certified labs required for testing and certification.

The USDA hemp farming rule will allow farmers to grow as much hemp as required for CBD (if not more) but how soon the market for CBD consumer products grows is subject to other rulemaking. CBD is unlikely to reach its full market potential as a food ingredient before the FDA, or Congress, makes a regulatory distinction between the amount of CBD in a single serving snack or beverage and the therapeutic amounts in prescription medications (Epidiolex, the first FDA approved drug containing a cannabinoid, came on the market in 2018).

Currently, most of the companies adding CBD to food and beverages are relatively small but risk-tolerant regional players. Every global CPG brand is formulating a CBD strategy and some are considering or entering the US market with their own products or through acquisition of incumbent companies even prior to FDA guidance. Similarly, the CBD market is unlikely to reach its full potential until the Treasury Department, or Congress, normalizes CBD sales. Though CBD is legal, companies still have difficulty obtaining routine banking services, such as payment processing.

The exuberance about the prospects for CBD over the next few years is entirely rational, but CBD is just one of the 113 known cannabinoids. One of the others, THC, is the basis of the multi-billion dollar legal cannabis industry. Another, CBG (cannabigerol) is a strong contender to be the next cannabinoid on the market. What little is known of the other cannabinoids points to promising therapeutic applications. The global pharmaceutical industry, like the global CPG industry, is ready to invest in hemp and cannabinoids as soon as the regulatory picture becomes clear and some have begun R&D to get ahead of that timing.

USDA takes the long view

What USDA repeatedly makes clear in the rule is that hemp, outside of the strict requirements for lab certification, is just another legal crop free to find markets and cross borders.

There are no restrictions on hemp seed import/export, which means US farmers can purchase seed on the international market and US cannabis biotech companies are free to export seeds. The rule explicitly states “there’s no need for additional regulation on biomass, fiber, seed, hemp seed oil or hemp seed for consumption.”

The rule sets the stage for US farmers to participate in a global hemp trade. The labs that certify hemp for THC content will also be able to certify it for export, so long as they are DEA certified. USDA, which actively promotes American crops on global markets, will do the same for hemp. “Should there be sufficient interest in exporting hemp in the future, USDA will work with industry and other Federal agencies to help facilitate this process.”

The regulation in many ways clears regulatory barriers to import/export of hemp-derived products. It is reasonable to see this as good for free trade in CBD. The first export of US CBD products was shipped to Mexico at the end of last July.

What about the rest of the plant?

The 90 percent of the hemp plant that yields no CBD (or other cannabinoids) may someday be at least as valuable as the 10 percent that does. In 1938, Popular Mechanics extolled hemp as The New Billion Dollar Crop (which is about $18 billion now) based solely on its value as fiber. Though farmers in 1938 could have used a valuable new crop, the Marihuana (sic) Tax Act was making the crop economically worthless. The farm economy hemp might have sustained was not allowed to take root.

The hemp farming rule begins to reverse that historic mistake. The potential for hemp as a source of food, fiber and plant-based industrial products is substantial. The Congressional Research Service found “The global market for hemp consists of more than 25,000 products in nine submarkets: agriculture, textiles, recycling, automotive, furniture, food and beverages, paper, construction materials, and personal care.” The relatively small existing markets for hemp fiber and hemp seed as food are more profitable per acre than the depressed prices for corn and soybeans.

There is reason to think future policies to address global climate change through “carbon farming” could benefit hemp agriculture. An Australian study concluded a hemp crop is “the ideal carbon sink” because hemp absorbs more atmospheric carbon per acre than any forest or commercial crop.

Products derived from hemp could have advantages in a future carbon-constrained economy. For example, concrete manufacturing is one of the largest industrial sources of C02 emissions globally but hempcrete, a product few people have heard about, is a carbon-negative substitute.

It will be a while, perhaps a long while, before hemp is as common as cotton or hempcrete is standard in new construction. Hemp has a tiny market presence outside of CBD and hemp seed as a food, and its lobbying presence is no larger. The future of hemp as a large and growing market is nonetheless very promising. As more and more hemp is harvested each year it is all but inevitable that entrepreneurs and investors will take on the challenge of bringing entirely new product categories to market.