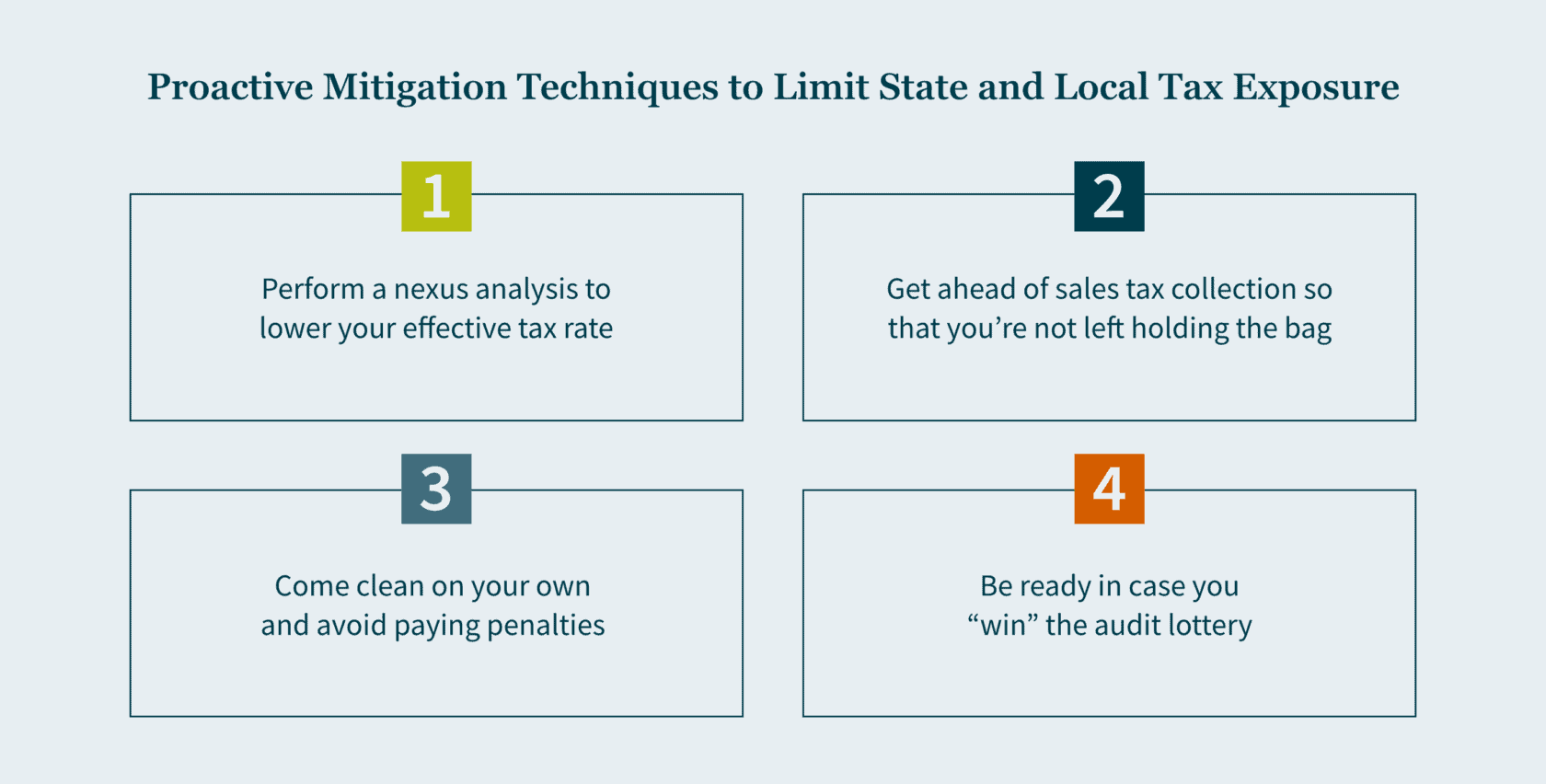

Proactive Mitigation Techniques to Limit State and Local Tax Exposure in a Recession

Executive summary

- Now that a recession seems imminent, it’s important to prepare by adopting state and local tax planning techniques now.

- These techniques include performing a nexus analysis to lower your effective tax rate; getting ahead of sales tax collection so that you’re not left holding the bag; coming clean on your own to avoid penalties; and being ready to win in case you “win” the audit lottery.

- Right now, you should be taking proactive measures to avoid overexposure and capitalize on opportunities that limit your overall tax burden.

Despite a seemingly robust economic recovery from the COVID-19 downturn, we are now looking down the barrel of another recession. When polled for a Wall Street Journal survey, more than three in five economists predicted a recession will occur over the next year due to a variety of reasons: inflation has hit a 40-year record high, the Fed has raised interest rates to the highest levels in more than 15 years, and several Fortune 500 companies have implemented mass layoffs. In addition, market volatility prompted by the implosion of Silicon Valley Bank and Credit Suisse has sent regulators around the globe into damage control.

While no one can predict the future — and if the COVID-19 pandemic has taught us anything, it is that the economy won’t follow the course of even the most prescient prognosticators. To prepare for the proverbial rainy day, in the following our State and Local Tax team details state and local tax planning techniques you can adopt now.

Technique #1: Perform a nexus analysis to lower your effective tax rate

Typically, a nexus analysis is performed “defensively” when you’re under the threat of an audit or to identify potential tax exposure ... and that usually means an increase in state tax. But you should also consider performing a nexus analysis “offensively” as a method for lowering your effective tax rate – either by capturing net operating losses (NOLs) in states where you haven’t previously filed or by lowering apportionment in high-tax jurisdictions.

This first idea rests on the principle that you can’t claim NOL deductions on returns you never filed. If your company historically operated at a loss (for tax purposes), a nexus analysis might not have been on your radar; or maybe you had a nexus analysis done, but then decided not to file returns where there wasn’t a material exposure. But if in 2022 or later years, you were or expect to be profitable and you’ve been doing business online or in multiple states, identifying potential prior year state income or franchise tax filings may allow you to claim the benefits of the federal NOLs on your state returns by carrying the losses forward to offset current or future taxes.

Note, current federal rules allow you to carry NOLs forward indefinitely until the loss is fully recovered, but they are limited to 80% of the taxable income in any one tax period. States do not always follow these rules, and moreover, state apportionment rules will affect how much of the NOL is allocated to a given state. Therefore, you’re not likely to see a “one-to-one" application, and you may still owe some taxes, but under the right circumstances, this technique will go a long way towards mitigating exposure for state income taxes that you may owe in the future.

Another way that increasing your state tax filings may decrease your state tax liability is by taking advantage of “economic nexus” developments to “spread out” your state tax liability across jurisdictions where rates may be lower (i.e., reducing your “effective tax rate”). Many states impose “throw-back” rules that require you to treat sales to states where you don’t pay taxes as if those sales should be sourced to your home state. But if, under economic nexus, you should or could be paying tax in those jurisdictions, you may be able to reduce the payment in your home state. Similarly, differences can arise between state’s rules for sourcing sales of services or intangibles that may be particularly helpful when considering how to treat a large item of gain from a sale of a business asset (e.g., stock in a subsidiary, or a valuable piece of intellectual property).

A few example scenarios illustrate these techniques:

- SoftDev Corp. started developing a SaaS product in 2019 and then testing its prototype apps online. They have employees that work remotely from home offices in five states. While SoftDev had potential nexus due to the economic activity in several states and payroll in the other five states, they only filed in their state of corporate domicile because sales were not significant, they had losses on their federal return, and the cost to prepare the other returns exceeded their compliance budget. In 2022, SoftDev expanded its product offering and began seeing significant sales in all 50 states. For federal tax purposes, they have accrued a large NOL that will reduce taxable income for the year (and probably several years to come). It would be wise to perform a nexus analysis at this point to identify whether SoftDev can capture any NOLs in other states – the key qualification being whether there is significant apportionment in the prior years as this will drive the amount of NOL available.

- Cal Widget Co. sells widgets (tangible personal property) it manufactures in California to customers all along the west coast and all its operations, including its one warehouse, are in California. Historically, Cal Widget only files a return in California, where it has 100% apportionment because of the throwback rule, and thus pays 8.84% on all its taxable income. However, by filing in additional states, the throwback rule would not apply to those sales, and thus they wouldn’t be “thrown back” to the California numerator of the apportionment formula. Even without paying tax to the other state, if Cal Widget could show that they would have owed tax under California’s rules, but for the fact that the state does not apply tax under those circumstances, the sales could still be removed from the California numerator. For example, if 50% of sales were to California customers, 25% went to customers in Oregon (average rate = 7%), and the remaining 25% went to Washington (no corporate income tax), using this method, Cal Widget could reduce its effective state income tax rate from 8.84% to 6.17%.

- Big Apple Co. has found a buyer for its signature logo and is anticipating a major gain event in 2023, and they realize that based on prior years, they’ll be paying New York State and City tax on the entire amount of gain because it’s the only state in which they’ve ever filed state income tax returns. If they are proactive, though, they can identify multiple states in which they have received revenue and can justify filing based on “economic nexus” and “market-based” sourcing principles – this won’t change New York’s tax rate, but it will provide a reason to apportion more of the income to source outside of the state and could save significantly on their tax bill.

Oftentimes, businesses are reluctant to really dig deep into nexus issues because they’re afraid of what they might find. And they end up waiting to take action until after they receive notices or their auditors (or worse, potential buyers) start asking about uncertain tax positions and accruals. But a slow-down in business due to the recession may offer you the opportunity to catch up on these nexus issues proactively.

Technique #2: Get ahead of sales tax collection so that you’re not left holding the bag

In a perfect world, when a company is properly accounting for, collecting, and remitting sales tax, there should be no (or at least very little) effect on revenue. Sales tax shouldn’t cost the business anything – instead, the business’ customers should be economically liable for the cost, while the business itself is only responsible for reporting and remitting the tax to the appropriate tax authority.

Problems arise when the business fails to account for sales tax and then only discovers the liability after the transactions have occurred and when it is no longer feasible to collect the individual sales tax amounts from customers. Then a cost that you could have passed through to your customers becomes your cost.

If you're not currently collecting sales tax, you might consider a few of the "red flags" below:

- Your business generates revenue online through a website, Software-as-a-Service, or another cloud-based product.

- Many states treat SaaS (and similar cloud-based products) as they would other types of software, which are generally taxable.

- What's more, since you're selling online, you may be subject to "economic nexus" without ever creating a physical presence in the location.

2. Your business processes payments online on behalf of other businesses making retail sales.

- Since you are the party processing the transaction, you may be required to collect sales tax as a "marketplace facilitator," even though you're really just a company providing services to other businesses.

3. Your business provides services, so you haven't really been concerned about sales tax in the past because you know it generally only applies to tangible personal property (TPP) ... but consider whether:

- You make some related sales of TPP when you are providing services (e.g., you design custom web infrastructure and occasionally sell specialized hardware to meet your client's specifications);

- The services you sell are computer programming and the end-product is typically custom software;

- One division of your business is leasing goods from another division; or

- Your services are taxable because they are dependent on, or related to, sales of TPP (e.g., third party software maintenance).

You can avoid this pitfall and ultimately save money by being proactive about identifying potential sales tax requirements and implementing systems to ensure you are properly collecting the tax.

Technique #3: Come clean on your own and avoid paying penalties

If your business sells products or services in multiple states, you could face unexpected tax liabilities for failing to comply with each state’s various income, franchise, gross receipts, sales and use, property, or other taxes. You may already be aware of the issue, and maybe you even have an accrual for the liability. And compounding any such liability are the interest and penalties that could be asserted if the state eventually discovers the business activity. But you don’t have to wait for the state to come after you, and if you’re proactive, you’ll probably be able to mitigate or remove all the penalties.

Virtually every state has a Voluntary Disclosure Program, under which you can execute a voluntary disclosure agreement (VDA) between your business and the tax authority to limit your liability for back-taxes. One benefit is that the VDA will limit the “lookback” period (otherwise a state can look back as far as the business had activity); this will often reduce the potential tax liability itself. Another benefit of a VDA is that any penalties that might have applied for late filing or payment are waived (though interest usually still applies). Finally, by going through the VDA process you are put in contact with a tax authority representative who can help you to determine precisely what rules apply to the business – they won’t exactly be a “tax adviser” but sometimes simply getting a hold of someone who will address your questions is challenge. And the certainty you will get from the process will give you comfort that your tax compliance process going forward is correct.

On top of state VDA programs, many states will offer amnesty programs. They usually are only available for a brief period (e.g., six months), have similar terms to a VDA, but are more relaxed in terms of eligibility. Let's say you’ve been filing for five years, and you stop doing business in a certain state. You receive penalties and notices, and you ignore them — you aren’t doing business there anymore. But during the recession, you need to expand back into that state for additional customers. If you want to resume your business there, an active amnesty program may allow you to set up shop without having to pay penalties on the missed filings.

With the country entering a recession, business profits are likely to decrease, and so too will state revenues; under these circumstances, state governments are more likely to offer these amnesty programs as they seek to expand the tax rolls. Be on the lookout if a VDA isn’t an option for you.

Technique #4: Be ready in case you “win” the audit lottery

Not only do state governments seek out delinquent taxpayers through amnesty and VDA programs during a recession, but they may also seek out additional tax revenue through audits. For state income taxes, we’re likely to see a surge in audits surrounding online work and remote workers because of increased popularity in remote work over the last few years. In addition, states perennially test a business’ “unitary” status (i.e., whether a given item of income should be apportioned between several states or allocated to the corporate domicile) and therefore any significant sales of business assets in the last couple of years may make you a target.

Ultimately, this is the time to be more introspective: look back on your last few years and figure out if you had any gaps in recording. If there are opportunities to capture NOLs or other additional savings, bookmark those too. It’s best to be prepared, because while there’s no guarantee you’ll be met with an audit, there’s no question that state governments increase their audit activity during a recession.

How MGO can help

A recession affects everyone, and state and local governments are no exception — which, in turn, affects you and your business. These techniques can help you prepare for whatever’s coming, ensuring you’re ready for potential audits and losses along the way. MGO’s State and Local Tax team provides experienced guidance to help you avoid overexposure and capitalize on opportunities that limit your overall tax burden.